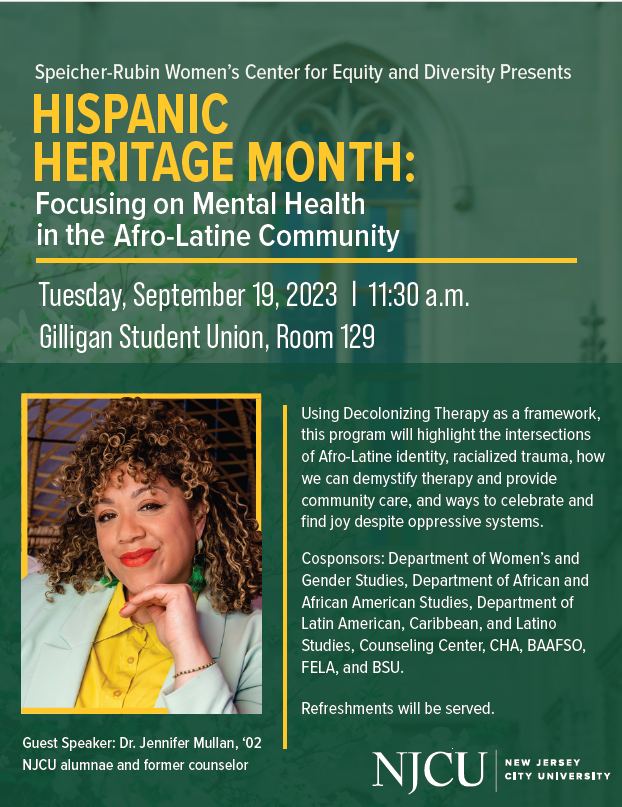

Selling the Drama

Behind the Scenes in New Jersey’s Indie Wrestling World

July 25, 2016

“Die Tella Die!” are probably the last words anyone would expect to hear resonating through the empty halls of a Catholic high school on a Saturday night. However on March 12th, 2016, this maddening mantra could be heard at Marist High School in Bayonne, New Jersey. An estimated crowd of 200 people dot the school’s gymnasium, all there for the same purpose: to see a bunch of guys beat the shit out of each other. At half court, a wrestling ring that looks like it has seen its fair share of body slams stands empty, save for a 16 year old referee. An instrumental of Alice in Chains’ “Would” plays over the loud speaker for the tenth consecutive time as all eyes in the room are fixed on a set of doors at the back of the gym. The crowd is getting restless, chomping at the bit waiting for the event to begin.

The man the crowd is clamoring for is John Patella, a 24 year old manager at a “big box” home improvement store. Standing at 6’6 and weighing in at 265 pounds, Patella will tell you he was destined to enter the professional wrestling world. “Presence is a huge part of wrestling. My size automatically makes me stand out,” Patella said. “Now don’t get me wrong, there are a lot of guys in the business who are five foot whatever that are outstanding showmen. Some of the high flying shit they do, that’s not me. I draw crowd reaction through manhandling them.”

Patella, known as “John Tella” in the indie wrestling circuit, is what the wrestling world refers to as a “heel.” He’s the guy the crowd loves to root against. He doesn’t high five little kids on his way to the ring; he takes their homemade signs and rips them into confetti. He reacts to the crowd’s jeers by yelling back at them. He’ll counteract a “Tella, you suck!” with “But your mother loves me!” He is booed at every event, no matter where it takes place and he wouldn’t have it any other way. The more heat the audience throws his way, the more it solidifies his character as a heel.

Anthony Velez, 28, is an inspector/installer at BMW North America. He made the decision to join the indie scene four months after Patella decided to throw his hat in the ring. Velez doesn’t have the height advantage Patella has, standing at just 6 feet tall. To standout, he had to come up with a strong gimmick. Enter the character “Tony Price”. Velez describes Price as “a scumbag trust fund baby who believes he is superior to everybody.”

To sell his character even further, Price has a man servant known only as “The Help,” an African-American man donned in a tuxedo. The Help is there to do whatever Price tells him to: wipe his sweat, hold his gum, and shine his shoes. The role of The Help is controversial and tends to conjure up images of old Hollywood, an age when African-American actors were cast to provide little more than comic relief. Hell, the character even shares his name with a 2011 movie about African-American maids in racially charged 1960’s Mississippi.

Marcus Jones, the man portraying The Help, has been good friends with Velez for the past five years. He pitched the idea to Jones in the weeks leading up to the Bayonne event. “I was a little apprehensive at first,” Jones said, “but Anthony broke down the character for me and I went along with it as a favor to him. To help develop his character, you know?”

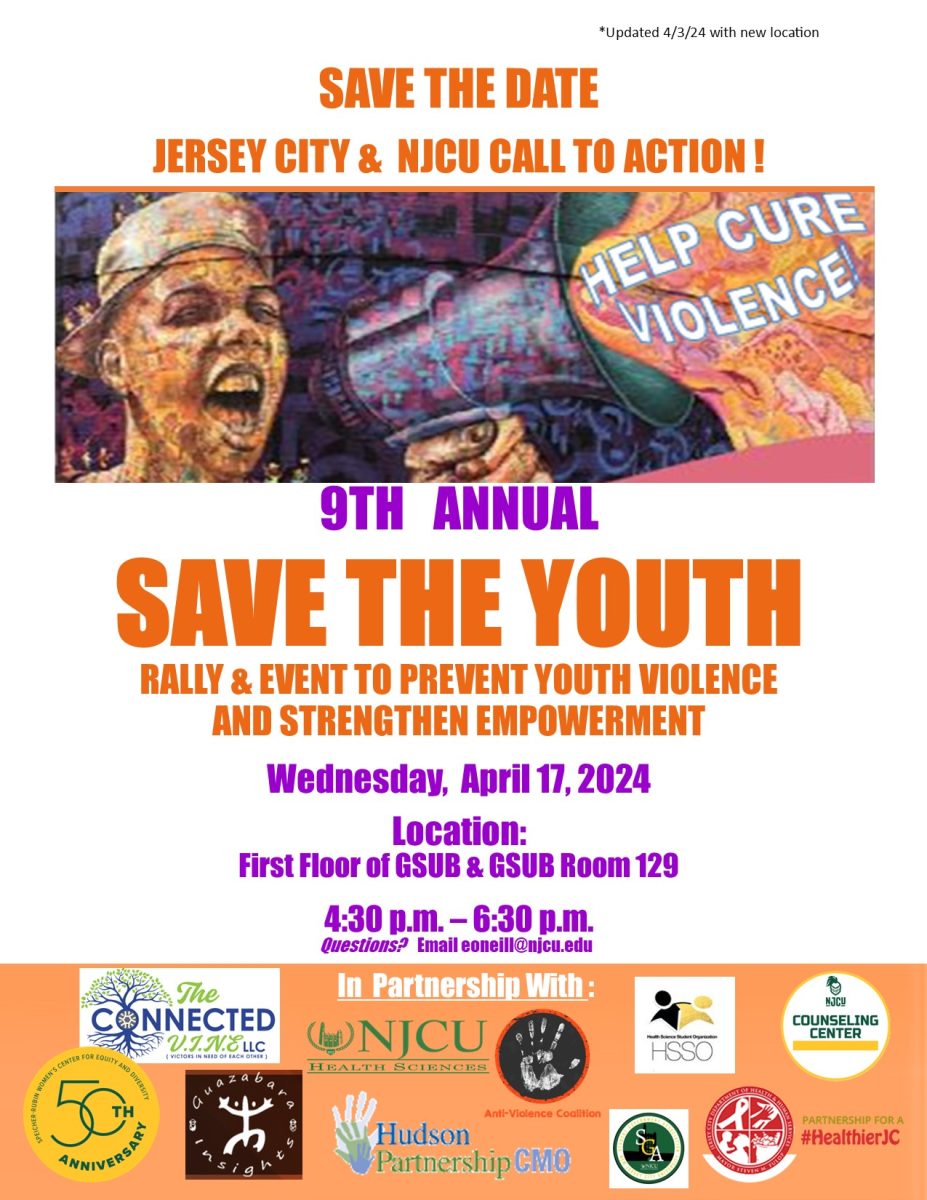

Patella and Velez wrestle for East Coast Professional Wrestling (ECPW), a wrestling company based out of Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey. “I looked at a lot of different training facilities…in Brooklyn, south Jersey, Staten Island,” Patella said. “ECPW had a good facility and had more to offer.”

“We decided to take a drive out to the facility one day to check out the company. We both liked what we heard and we signed the contract that day,” Velez added.

The contract they each signed states that they are responsible for paying $3,000 for the professional training they receive. In return, they get to showcase their talent at live shows. Also stated within the agreement is that the company is not responsible for any injuries incurred. Needless to say, Patella and Velez are covered with insurance through their jobs.

ECPW founder and owner, Gino Caruso, has been training and preparing people for professional wrestling for the past 25 years. To say that this guy knows what he is doing is an understatement. Caruso is a seasoned veteran, having wrestled in nearly every major facet of the industry under the name “Mr. Italy.”

On Saturday mornings, Patella and Velez make the 40 minute drive from Bayonne out to Caruso’s facility to hone their skills in the ring. This is the only day the two are available to squeeze in ring training due to obligations outside of wrestling. They both work full time. Velez also goes to school and has a 7 month old daughter at home (who happens to be Patella’s goddaughter).

From the outside, the building looks like an old furniture warehouse. Aside from the wrestling memorabilia and photos at the top of the stairs inside, first impressions of the place don’t scream “training facility” but then you hear the wooden boards reverberating against the ring’s steel frame followed by a deep groan. Someone just got slammed.

The five people standing outside of the ring turn to shake hands with Velez and Patella when they walk in. It’s a sign of mutual respect among the wrestlers. Anytime someone shows up to the facility or leaves for the day, everyone in the room shakes their hand. Even if you’re not particularly fond of someone else, you still shake their hand.

The large room where they train is reminiscent of an underground fight club, a testament to the grittiness of the sport. The word “ADRENALINE,” crudely spray painted in Hulk-green, adorns one of the black concrete walls. Cell phones, gym bags, water bottles and a handful of spectators occupy the shoddy wooden bleachers that line the walls of the space. Several ECPW banners and an American flag are hung throughout the room.

Velez and Patella set their bags down before jumping into their respective warmups. Velez stretches his legs out on the bleachers while Patella knocks out several fast paced pushups. Individually, they enter the ring and intentionally throw themselves down hard on the mat. These practice falls allow their bodies to become accustomed to the impact.

Caruso tells Patella and Velez to run through a few rehearsed segments. They start with basic moves like grappling and throwing each other into the ropes. Patella throws Velez into a corner and proceeds to chest chop him a few times. Caruso offers them advice on how to make it more believable. He tells them to run through it again, but to reverse the roles. With Patella now in the corner, Velez returns the chest chops. “Better,” Caruso assures them. “Keep running through the routines.” He heads upstairs to his office, leaving them to run through different moves on their own.

They hop out of the ring. Velez is grimacing. “My fucking side, man,” he says. He lifts his shirt, exposing his green and dark purple bruised ribs. “They’ve been like this for the past month or so.” Patella jokingly tells him to suck it up and hops back in the ring to run through drills with one of the younger wrestlers. Velez makes the call to sit out the rest of the practice session, hoping that his ribs will heal up in time for his first live event: the Bayonne show.

Skeptics of entertainment wrestling will often denounce its authenticity, making statements like “How could you watch something so fake?” The condition of Velez’s ribs, however, is a visual reminder that it is not entirely phony. Yes, the outcome of matches are almost always pre-determined. And no, these guys aren’t out there to intentionally hurt each other, but the injuries are simply inevitable.

“It’s entertainment but the hits, bumps, bruises, cuts, [and] blood [are] all real. Then people say dumb shit like ‘I don’t watch that shit, it’s fake,’ as if Game of Thrones is a real fucking thing being shown by the news,” Patella said. “People are fucking stupid.”

The payoff of their hard-nosed training arrives three weeks after the aforementioned training session. Velez is confident that his ribs have healed enough for him to participate in the event. “There’s no way in hell I was gonna deny the world the debut of Tony Price,” Velez, or perhaps more accurately, Price said.

The Bayonne event at Marist High School kicks off with a match featuring Shane “The Franchise” Douglas, a revered character of wrestling’s yesteryear. As he makes his way to the ring, the crowd is split in their reaction. Some of the older fans in the crowd cheer for him while others taunt him with chants of “What?”a catchphrase coined by one of the biggest names in the history of the sport, Stone Cold Steve Austin. Once inside the ring, Douglas begins to chastise the crowd with a tirade.

“That’s what explains it to me, when I come out here as a professional wrestler for 37 years, and I hear morons talking about some tag line from a sports entertainment company back in the 90’s,” Douglas said. “I made my mark in this business not because I put my lips on Vince McMahon’s rear end … I walk through a doorway and come out here and I have people saying ‘What? What?’… and you wanna know why our business is in the condition it’s in.”

Douglas’ remarks about the state of professional wrestling suggests what many of the industry’s top pundits think about the direction the upper echelon of the business is heading in. In a 2015 blog, Jim Ross, an announcer treasured for his overzealous commentary, voiced his expert opinion on wrestling’s current state of affairs.

“Wrestling is best when it comes from a logically, realistic place and is executed inside the ring as an athletic contest built on common sense and not an acrobatic show that exposes the business as a sham with no selling and the complete lack of some talent’s ability to properly apply an actual wrestling hold.” Further on, Ross said “I want the business to be healthy and to prosper long after I’m gone for future generations to enjoy. At the rate some of the things that I’m watching each week on TV are happening, I’m not [so] sure that’s going to occur.”

While bigger promotions of wrestling like the WWE have recently been affected by watered down plots and overacting, independent leagues like ECPW tend to rely more on the physicality of the sport. That is not to say, however, that the promotion’s wrestlers lack character.

The emcee of the show introduces the next match in a bland tone. A bingo caller at an old folk’s home has more gusto than this guy, but it is the most anticipated match of the night. Tella is on. Fortunately, the crowd and Tella make up for the announcer’s lack of enthusiasm. Tella walks out to an instrumental of D12’s “Fight Music,” dressed in all black, hood up, swagger in full effect. He grabs his crotch at the crowd as they heckle him, shouting “John Tella sucks!” in unison. On the way to the ring, he rips up a little kid’s homemade sign (as previously advertised) and slaps the man that tries to defend the kid. He spits his gum into the crowd and it hits someone in the face. All of this happens before the match even starts.

He towers over his opponent, Sinister Wynn, and proceeds to toss him around like a ragdoll for a good portion of the match. The crowd demands something more. “Do something else!” they chant. They’re always chanting something. Tella knows it’s time to turn up the heat. He clothes lines the guy after springing off of the ropes. The crowd winces, then begins a predictable chant of “That was crazy!” His opponent stands up and they begin to exchange blows. Tella managed to sneak a pair of brass knuckles into the ring in his side pocket. While the referee isn’t looking, he puts them on and knocks Sinister out cold (simulated, of course). Fight over. “You’re a cheater” erupts from the crowd. Tella mocks the room as he makes his way out of the gym.

Tony Price’s match was a bit different. In his first live bout ever, Price is part of a 13 man Battle Royale; the last man left standing in the ring is deemed the winner. One by one, the wrestlers enter the ring. Price, sporting sunglasses, a black tank top, and red shorts, is the last to enter. While he hasn’t had enough time to build up the fan base Tella has, a few people from the crowd yell “The Price is wrong! You suck!” Price orders The Help to open the ropes for him as he enters the ring.

What ensues is a brilliantly chaotic, disorganized mess of a match. A guy who looks like a vampire smacks someone across the chest, turns around, and gets slapped back by a completely different person with blue warrior face paint on. Behind them, a guy in a Canadian flag-inspired spandex costume choke slams another guy wearing pants with flames running down each leg and the name “Chico” displayed across the ass. You can’t make this shit up.

Price holds his own in the back corner of the ring, exchanging blows with two guys twice his size. The Canadian gets tossed out of the ring, then another until there are only 3 wrestlers left. Price is one of them. As the other two plot to team up against him, Price yells “Wait, let’s think about this!” The wrestlers look at each other before simultaneously drop kicking him in the chest. Stunned, Price gets desperate. He uses The Help to his advantage and has him pull one of the wrestlers out of the ring. While the remaining guy complains to the referee, Price knocks him over the top rope and out of the ring. Tony Price wins.

Both Tella and Price had the honor of winning their respective matches in their hometown in a seemingly dishonorable way: they both cheated. However, cheating is not only tolerated in wrestling, it is often encouraged. It is engrained in the “heel” culture and an integral part of selling the drama of wrestling. Tella was once filmed after a match telling a group of kids “You do whatcha gotta do to win,” as they collectively accused him of cheating.

At the end of the night, after the crowd has gone, close friends and family stay behind to chat and take pictures with one another. The wrestlers fold chairs and dismantle the ring, loading everything into the back of a box truck. Before leaving, they congratulate each other on a successful show, some with hugs and others with handshakes.

What the future holds for these budding ringsmen is in large part up to them. Their level of commitment and desire to be great will play an integral role in their individual successes in the business.

Patella sees wrestling as more than just a side gig and is determined to make it to the top tier of the business: “I want to be able to make a comfortable living just wrestling, and be able to pay all my bills without having a regular square job. The major goal is I want to go to WWE.”

Velez is deciding to take a more cautious approach regarding his future with wrestling: “Making long-term goals is great, but I try not to look too far ahead into my career as a wrestler. I want to master my craft… and take the Tony Price character to the level of success I have envisioned for him. Once I’m fully done with the initial training, I’ll re-evaluate my goals and take it from there.”

As for Jones, he sees no future for himself in wrestling. However, he has his heart set on another combative contact sport: “As I said, this was just a favor for a friend. I plan on taking up mixed martial arts, but first I want to complete EMT school.”

Whatever the outcome or however brief their stint may be in the profession, these three have become and will forever be, if only by association, a permanent part of the culture of entertainment wrestling.